text by Roger Fernay

- French

- English

Original Text

C'est presque au bout du monde

Ma barque vagabonde

Errante au gré de l'onde

M'y conduisit un jour

L'île est toute petite

Mais la fée qui l'habite

Gentiment nous invite

A en faire le tour

Refrain:

Youkali, C'est le pays de nos désirs

Youkali, C'est le bonheur, c'est le plaisir

Youkali, C'est la terre où l'on quitte tous les soucis

C'est, dans notre nuit, comme une éclaircie

L'étoile qu'on suit, C'est Youkali

Youkali, C'est le respect de tous les voeux échangés,

Youkali, C'est le pays des beaux amours partagés,

C'est l'espérance Qui est au coeur de tous les humains,

La délivrance Que nous attendons tous pour demain

Youkali, C'est le pays de nos désirs

Youkali, C'est le bonheur, c'est le plaisir

Mais c'est un réve, une folie,

Il n'y a pas de Youkali!

Et la vie nous entraîne

Lassante, quotidienne

Mais la pauvre âme humaine

Cherchant partout l'oubli

A pour quitter la terre

Su trouver le mystère

Où nos rêves se terrent

En quelques Youkali....

Refrain

Text by Roger Fernay

Translation

It was to the end of the world

my vagabond boat

rocking at the oceans will

led me one day.

It's a small island,

but the fairy that lives there

kindly invites us

to take a tour.

Refrain:

Youkali, it is the land of our desires.

It means joy and pleasure,

Youkali, it is the land where you leave your cares behind

It is, in the night, like a beacon,

A start that we follow, that is Youkali

Youkali, it is where we keep out promises,

Youkali, it is the land of mutual love,

It is the hope in all human hearts,

The deliverance we all wait for.

Youkali, it is the land of our desires.

It means joy and pleasure,

But it is a dream, a folly,

There is no Youkali!

And life, tedious and banal,

drags us along.

Yet the poor human soul,

Searches everywhere

to find the land

Where hide our mysteries

Where our dreams lie

In some Youkali....

Refrain

Translation by James Benjamin Rodgers

A Land of our Desires

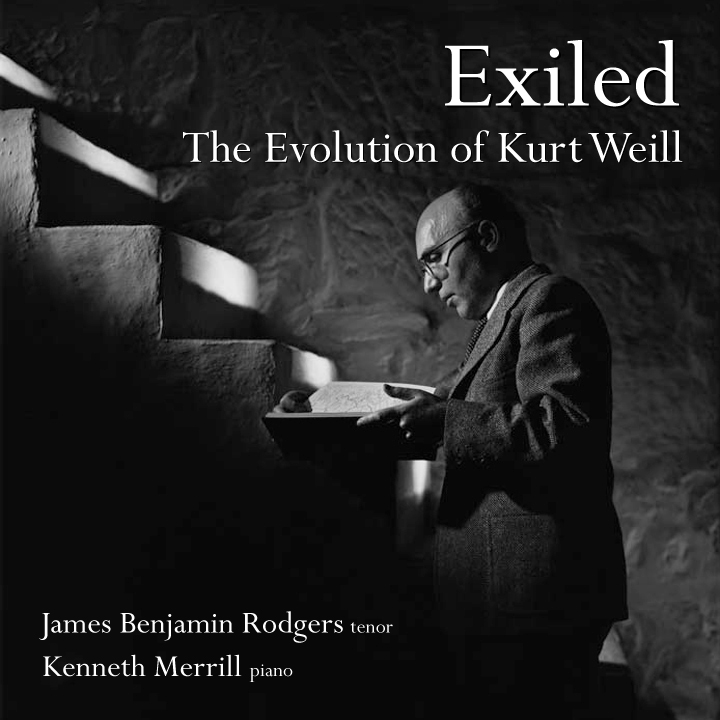

Despite some degree of success in Paris, Weill’s financial situation had become dire. Due to strictly enforced Nazi legislation, it was impossible for Jews to access a German bank account without Nazi permission, which was rarely granted to anyone. Furthermore, all Jewish cultural activities had been banned. This eliminated any royalties Weill’s works had been generating. In another example of the passive approach taken by many throughout these early years of the Nazis rise, in November 1933, Weill’s publisher, cancelled his contract and ceased his monthly stipend payments. Weill had entered Paris hopeful of retaining some measure of the financial security it had taken him years to establish. He was to be disappointed. At the hands of the Nazis both his assets and his regular income vanished almost overnight.

Thankfully, the month before Universal cancelled his contract, Weill had managed to sign a new publishing agreement with Heugel in Paris, which guaranteed an advance of 4,000 French francs per month. Whilst not a lot, this gave him some financial breathing room. Having been temporarily hosted in a comfortable Paris apartment he ultimately found a little stone house in the outer Parisian suburb of Louveciennes. He lived there for the next two years giving him the stability he needed to continue composing.

Unfortunately the resolution of one problem led to the emergence of another. On November 26th, 1933, French soprano Madeleine Grey performed three songs from Der Silbersee at the Salle Pleyer with Maurice Abravanel conducting the Orchestre de Paris. Grey’s performance received enthusiastic approval. However, amidst the triumphant applause, local French composer and music critic Florent Schmitt led boisterous cries of: “Vive Hitler!” Weill was distraught. This first hand encounter vividly illustrated the harsh reality that Anti-Semitism was by no means confined to Germany. However, this shameless display of contempt for a Jewish composer was not exclusively about Anti-Semitism. Conductor Maurice Abravel recalled: “That reaction put in the open the envy and the jealousy of French artists.” Weill began to realize that the enormously territorial French musical establishment would never accept him into their fold. He would perpetually be held at arms length, a musical curiosity to be viewed with some degree of suspicion. Paris, it turned out, was not the kind of compositional environment for which Weill yearned.

In 1935 Roger Fernay wrote lyrics for the instrumental waltz from Marie Galante, one of Weill’s most hauntingly seductive melodies. Fernay’s words could not have been more significant, vividly capturing the essence of a hopeless search for “the land of our desires”. Weill’s own search for such a sanctuary would continue.