text by Kurt Weill

- German

- English

Original Text

Ich frage nichts.

Ich darf nicht fragen,

Denn du hast mir gesagt: "Frage nicht!"

Aber kaum höre ich deinen Wagen.

Denke ich: Sagen, oder nicht sagen?

Er hat alles auf dem Gesicht.

Glaubst du denn daß nur der Mund spricht?

Augen sind wie Fensterglas.

Durch alle Fenster sieht man immer,

Schließt du die Augen ist es schlimmer.

Meine Augen hören etwas,

Etwas anderes meine Ohren.

Für Schmerzen bin ich denn geboren.

Laß mein Gesicht am Fenster, laß;

Die Sonne darf jetzt nicht mehr scheinen!

"Es regnet," sagt das Fensterglas.

Es sagt nur was es denkt!

Laß uns zusammen weinen...

...zusammen weinen...

Text by Kurt Weill

Translation

I don't ask.

I may not ask,

For you have said to me: "Don't ask!"

But I can just barely here your car.

I think: Say it or don't say it?

It's all on your face.

Do you believe that only the mouth speaks?

Eyes are like windowpanes.

Through each window, one can always see everything.

Close your eyes, it's worse.

My eyes hear something,

Something other than my ears.

I was born for pain.

Let my face lie on the window;

The sun may not shine any more now!

"It's raining," said the windowpane.

It says only what it thinks!

Let us weep together...

...weep together...

Translation by James Benjamin Rodgers

It's Raining

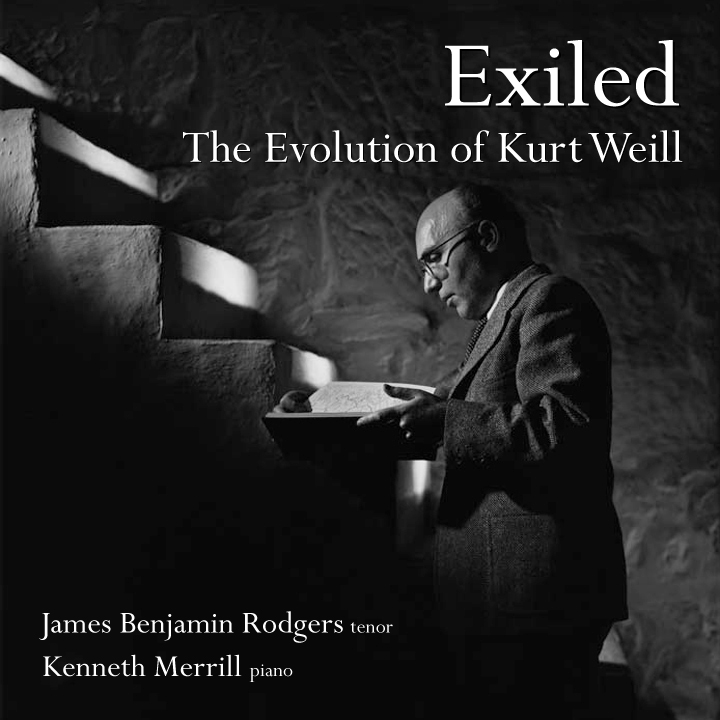

Der Silbersee’s main opening in Leipzig represented a final act of defiance by the German artistic community. As Hans Rothe recalled:

"Everyone who counted in the German Theatre met together for the last time. And everyone knew this. The atmosphere can hardly be described. It was the last day of the greatest decade of German culture in the twentieth century."

Just a few months later the core of Germany's artistic community was scattered to the four winds, forced into exile by the effects of what the Nazis labeled “the reorganization of German cultural activity”.

Likely because of its popularity and poignancy, Weill's work became a battleground for the increasingly arrogant Nazi sympathizers. On February 24th, the Berlin edition of the Völkischer Beobachter wrote: “One must treat a composer like Weill with distrust, especially when he, as a Jew, allows himself to use a German opera stage for his un-German purposes. The most shameful thing is that the general music director of the city of Leipzig, Gustav Brecher, has lent himself to such a performance! A man with any sensitivity would have rejected this kind of presentation! ” It went on to openly threaten the conductor of the Leipzig production: “Recently, at the commemorative celebrations, Mr Brecher scrutinized our Führer rather closely in the Gewandhaus ... Now he will come to know the Führer and the … power that emanates from him much better!”

Ironically, and representative of Weill’s hopefulness that this obvious crises in the German political system would soon be resolved, Weill wrote to Universal Edition on February 26th: “No one believes that things can go on much longer as they are.” Such optimism could not have been more misplaced. A day later, the Reichstag burned to the ground and the Nazis seized the opportunity to generate suspicion for their main political rivals the Communist Party. Hitler theorized that the fire was a signal, marking the beginning of a Communist revolt that would tear the country to pieces. With this the Nazis succeeded in turning the populace against their left wing rivals. On February 28th the Preussische Pressedienst (Prussian Press Service) reported: "this incendiary act is the most monstrous act of terrorism carried out by Bolshevism in Germany". The Vossische Zeitung newspaper said: "the government is of the opinion that the situation is such that a danger to the state and nation existed and still exists".

Mass uncertainty emerged amongst the German people and on February 28th, 1933, Hitler persuaded Hindenburgh to sign the Reichstag Fire Decree. This startling document restricted the personal freedoms of all Germans wherever communism was deemed to be a threat to the stability of the state. A portion of the decree’s first article reads:

"It is therefore permissible to restrict the rights of personal freedom [habeas corpus], freedom of (opinion) expression, including the freedom of the press, the freedom to organize and assemble, the privacy of postal, telegraphic and telephonic communications. Warrants for house searches, orders for confiscations as well as restrictions on property, are also permissible beyond the legal limits otherwise prescribed."

On March 4th, the Nazi’s used this legally obtained authority to close all three productions of Der Silbersee. With that, Weill’s music fell silent in the country of his birth for the next twelve years.

With his worst fears realized, Weill looked to Paris. Performances of his works had been successful there and he saw the French capital as at least a temporary solution for his ongoing work as a composer. Remarkably, in this moment of extreme turmoil, when even his safety came under threat, Weill’s primary focus remained his work. On March 14th 1933, just a few days before his ultimate exile, he wrote these remarkable words to his publisher:

"I find it quite wrong and indefensible to have you all sitting in Vienna and moping instead of doing the only thing possible under today’s circumstances: to go abroad and explore all the possibilities for finding new markets for (my) works; to establish new contacts, track down or create new performance opportunities. Why aren’t you in Paris now…?"

On the 21st of March , 1933, Weill caught wind of his imminent arrest. Having made the necessary preparations for a swift departure, he drove to the French border with Casper and Erika Neher, crossing into France with five hundred francs and a small suitcase. He would never return to Germany. Two days later the Reichstag, firmly under the control of the Nazis, passed the Enabling Act of 1933. This special law granted the Chancellor the authority to pass laws without the involvement of the Reichstag. Thus, within the confines of the constitution, Hitler gained supreme power over the Weimar Republic.

Amidst all of this turmoil, one might wonder what had happened to Weill's wife Lotte Lenya? By 1933 Lenya and Weill's relationship had become somewhat strained. Weill, it appears, was having an ongoing affair with Erika Neher. (Her husband, Oscar Neher was a dear friend to Weill, was gay.) The affair would certainly have given Lenya cause for resentment. However, akin to Weill’s indiscretions, in 1932 Lenya had met the Italian tenor Otto Pasetti during a production of Weill’s Aufstieg und Fall der Sadt Mahagonny in Vienna. She began travelling with him and soon after applied for a divorce from Weill. It was granted on September 18th, 1933, with little if any resistance from Weill. Remarkably, and perhaps illustrative of the complexity of the relationship, their correspondence continued during this period and their emotional connection remained seemingly unbroken. They would ultimately remarry in 1937 and live together for the remainder of Weill’s life.

They were reunited in April of 1934, at the request of Edward James, an English philanthropist who was a big fan of Weill’s work. James had committed to underwriting the first season of Les Ballets, a new Paris based company founded by George Balanchine with Boris Kochno, and wanted to produce a new ballet starring his wife the ballerina Tilly Losch. The Seven Deadly Sins became the material for the ballet and the lead character of Marie was written for two women, a singer and a dancer. Lotte Lenya would take the singing role and the scandalous behavior continued as she reportedly had a love affair with Losch during the course of the production. To add to the intrigue, Otto Pasetti was also given a role in the male quartet for the piece. Weill approved this without hesitation. After all, Pasetti was a good tenor and would serve his work admirably. One wonders how Weill and Lenya could manage to function in a working environment given such circumstances? Fidelity seems to have been something of a trivial matter for the pair and though they were undoubtedly hurt from time to time, this period illustrates both the resilience of their connection and their tremendous capacity to put their difference aside in the interest of the work.

Weill, who always sought collaborators of the highest quality, hoped to engage Jean Cocteau as his librettist for Seven Deadly Sins. Although Cocteau declined the ballet, he and Weill met on several occasions. Lenya later reminisced:

"Kurt and I were invited to dinner at Cocteau’s one evening. Cocteau tried to speak a few sentences in German. Kurt expressed his surprise at this attempt and asked Cocteau if he really spoke German. Cocteau replied, ‘Yes --- all nouns!’ He then excused himself, went into another room, and returned a few minutes later with a sheet of paper. On it were the first lines of ‘"Es regnet".’ Kurt encouraged him to finish the poem, which Cocteau eventually did. Kurt corrected some of Cocteau’s grammar-school German and set it to music."

This heart-rending song vividly exposes the emotional state Weill must have found himself in, a man without a country, without a home, and with little idea what the future had in store.