text by Georg Kaiser

- German

- English

Original Text

Der Bäcker backt ums Morgenrot

Das allefeinster Weizenbrot.

Doch wer das Geld vergessen

Darf das Weizenbrot nicht essen.

Für ihn’s gibt’s kein Brot in der Not!

Refrain:

Schnalle deinen Gürtel enger um ein Loch,

Es geht noch, es geht ja immer noch.

Schnalle deinen Gürtel enger um ein Loch,

Erst denkt mann es geht nicht

und dann geht’s doch.

Wo liegt das blanke Silbergeld

Für das man Weizenbrot erhält,

Wir haben’s nicht vergessen,

Wir haben’s nie besses,

Für uns gibt’s kein Geld in der Welt.

Refrain

Und so vergeht die Lebenszeit,

Man war doch da; man war bereit.

Doch will sich wer beschweren, muß er hören

Was man ihm in die Ohren schreit.

Refrain

Text by Georg Kaiser

Translation

At sunrise the baker bakes

lots of fine white bread.

But he who forgets his gold

must go without.

Though in need, for him there is no bread.

Refrain:

Tighten your belt another notch,

it goes tighter and tighter.

Tighten your belt another notch,

you think it can't go any tighter,

but it does.

Where is the silver cash

that we can use to get the bread?

We have not forgotten,

we've never been able to possess it,

for the likes of us there is no money in the world.

Refrain

And in such a way passes a lifetime,

one was here and ready.

But he who complains must hear

their screaming in his ear.

Refrain

Translation by James Benjamin Rodgers

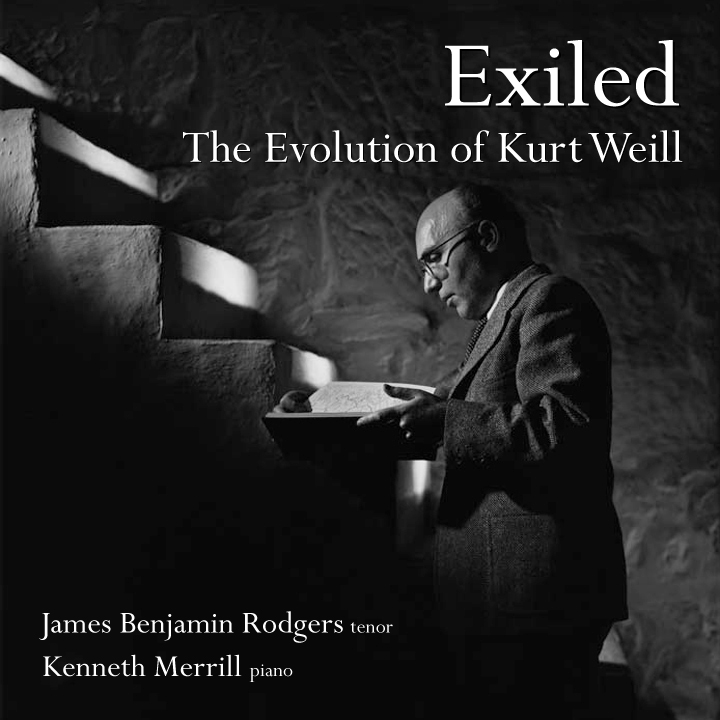

A Work Between Genres

Kurt Weill, always politically conscious, was under no illusions as to what a Nazi led government meant for a Jewish artist living in Germany. Yet in spite of the deteriorating social circumstances, he never failed to put his work as a composer first. Many years after his death his wife Lotte Lenya told a story from the earliest years of their marriage:

Kurt was always at his desk by nine . . . completely absorbed and like a happy child. This was never to change, as a daily routine I waited patiently at the table, Weill came down for meals, and then went back to his music. After a few days, I said to him, “this is a terrible life for me. I see you only at meals.” He looked at me through those thick glasses and said, “But Lenya, you know you come right after my music.”

Following the success of Three Penny Opera, Weill built an impressive catalogue of stage works. In 1932, on the back of that success, Weill and Lenya purchased a house in one of Berlin's most affluent suburbs. It was here that he received a disturbing note in the mailbox: “What’s a Jew like you doing in a community like Kleinmachnow?” This was just one of many veiled threats that would follow. In February Weill wrote to his publisher: “I think that what is going on here is so sick that it can’t last longer than a few months, but I might be wrong.” The atrocities that followed were beyond Weill’s imagination.

The following year, sensitive to the deteriorating political environment, Weill suggested the idea of a musical folk play. As he described: “It isn’t to be an opera, but a work between genres.” The idea of “work between genres” is something he would explore for the remainder of his life. Der Silbersee (The Silver Lake), set as a fairy tale, depicts a society devastated by unemployment, hunger and social chaos. There was little doubt in the minds of those who saw the work that this was a parody of their own failing republic. Early in Act 1, Severin sings of that which is unattainable for those without means: a simple loaf of bread.